Rajas of the Ganges is a brand-new worker placement and dice rolling board game from designers Inka Brand and Markus Brand. Published by HUCH! the game sees 2 – 4 players trying to accumulate both fame and wealth, with a full game lasting about an hour. Set in 16th century India, players take up the roles of nobles looking to expand their estates, whilst visiting the markets and palace next to the Ganges river. However, does Rajas of the Ganges manage to pull of the mixture of dice and karma? Let’s find out!

Unlike most games Raja of the Ganges has two separate point trackers for fame and wealth. The latter is easier to earn in bulk but the number of spaces on the money tracker is far greater than on the fame tracker. These two trackers run in opposing directions around the board, with the aim of the game to make your two markers meet or pass each other. This creates an intriguing dynamic where players can focus on either gaining large amounts of wealth, to zoom around the money tracker, go mostly for fame or both in a balanced fashion.

After setup each player will have in their possession an empty personal province board, a Kali Statue dice board, a single dice of each colour and three worker meeples. On the board they will also have a boat on the starting river space, a fame marker, a money marker, a karma cube and, last but not least, 4 upgrade cubes set to lowest state of the 4 buildings. It sounds a lot, and to be honest it is a lot, but after only a couple of turns it all becomes very clear.

The game is played out over as many rounds as needed until one players markers meet. Each round players will be placing their workers onto action spaces on the board. There are 4 main areas of the board: the palace, quarry, market place and harbour. The Great Mogul’s palace is in two halves. The first allows players to simple exchange a die of one colour for two dice of another pre-defined colour or gain a single die. For example, placing a worker meeple on the action space to gain 2 purple dice would cost an orange die. Whenever dice are received the player must instantly roll them to determine their pip values and add it to their personal Kali Statue. Only 10 dice can be stored by default though it is seemingly uncommon for someone to horde that many dice!

The other half of the palace has chambers that grant special actions. Each of these chambers require an exact pip value on a die to be spent when a worker is placed there. These range from the 1-pip Great Mogul himself, which gains the player 2 fame and the first player marker, through the likes of the Raja Man Sign, whom allows an upgrade cube to be increased in value, through to the 6-pip Portuguese, whom enables the player to zoom 6 unoccupied spaces along the river.

Another way to travel along the spaces on the river is to make your worker visit the harbour. After the first free harbour action space is taken each costs money on top of the normal charge of a die. To move 1 space along the river a die with pip value of 1 must be discarded, 1-2 spaces 2-pips and 1-3 spaces a 3-pip valued die. Don’t have one of these and the harbour action is unavailable to you. Why would you want to sail down the Ganges though? Each space along the river gains the player a bonus. These bonuses include earning fame based on the amount of karma you have, getting dice of any colour or a building upgrade. Only one ship can occupy a single space on the river at a time so until a ship moves it is essentially blocking that bonus for other players.

Next up is the quarry where a player goes to expand their estate on their personal province board. There are 10 quarry spaces which come with an increasing money cost. By playing a worker here, and paying the cost, a player can spend coloured dice for any of the top most province tiles. Each tile has a road and/or junction that connects one tile to another, though the only placement rule is that a new tile is linked in some way to the residence building. When a road leads from the residence to an edge of the province board a bonus, similar to the river spaces, is awarded. If any of the four special buildings are depicted on the province tile when built fame points are awarded: the number of fame is dependent on how upgraded that building is. Province tiles can feature 3 different types of markets.

Markets come in three forms: Silk, Tea and Spices. When these are built nothing special occurs but they can be activated by making workers visit the market place on the main board. A general market allows one of each type to be activated, gaining the money denoted on the tile next to the market. Type specific market action spaces are also available, costing the number of pips on a die equal to the number of markets you wish to trigger, earn the money indicated.

Once everyone has placed their workers out the round ends and all workers are reclaimed from the board, freeing up the used action spaces. If not claimed the first player marker moves clockwise to the next player and a new round begins. During the game there are ways for players to obtain addition workers, up to a maximum of five, allowing more actions to be done before a round ends. These are triggered when a player reaches certain points on the three trackers (river, fame and money). Once someone triggers the end of the game, everyone up to the starting player gets a final turn and then the winner is revealed.

Normally, dice add an unnecessary element of luck, where consistently defying the odds and rolling higher is a route to victory. To counter this, there are actions which require only a colour of dice to be performed. On top of this up there are action spaces which require different pip values on the dice. This results in the “best” result of the dice changing depending on what you want to be able to do. To further this, and to mitigate the randomness, there is an action space which enables the player to re-roll their dice. This is still a little luck based but is a step in the right direction. Then, there is the karma system.

Players can earn karma throughout the game by landing on specific river spaces, gaining bonus-like yield tokens or performing the 3-pip “Yogi” palace action. Players can store up to 3 karma points, which can be spent at any time to flip a dice over. This manipulation enables enough input to help players feel they are in control. Note that while players can gain karma via bonus tokens, in two player games you’ll most likely still have a few left untaken at the end of the game; while with any other player count there is a churn of tokens.

Coming from playing other titles revolving around dice management it was interesting to see that each colour dice is treated as equal. Trading in a single die of any colour gained you two dice of a pre-determined colour results in there being no progression to rarer dice. This meant that each was a viable choice, often seeing players sticking to a particular colour. Some change is encouraged to gain better province tiles, otherwise it seems better to obtain dice matching the colour of other dice already in hand. Competing for tiles does add in a wave of player interaction but people seemed to automatically stick to different colours.

There is a level of weight to Rajas of the Ganges, something made more daunting by the busy design of the central game board. The actions themselves are simple, as is the aim of the game, but it is the number of aspects players must simultaneously consider that will put some off. Forgetting the markets for a couple of turns can put you behind in money, not focusing on the province tiles can see a lack of personal board benefits and negate the river and see your opponents get a number of small but potentially effective bonuses. As long as you eventually focus on each aspect then you aren’t out of the game. Still, players do need to strike somewhat of a balance between the actions available to them.

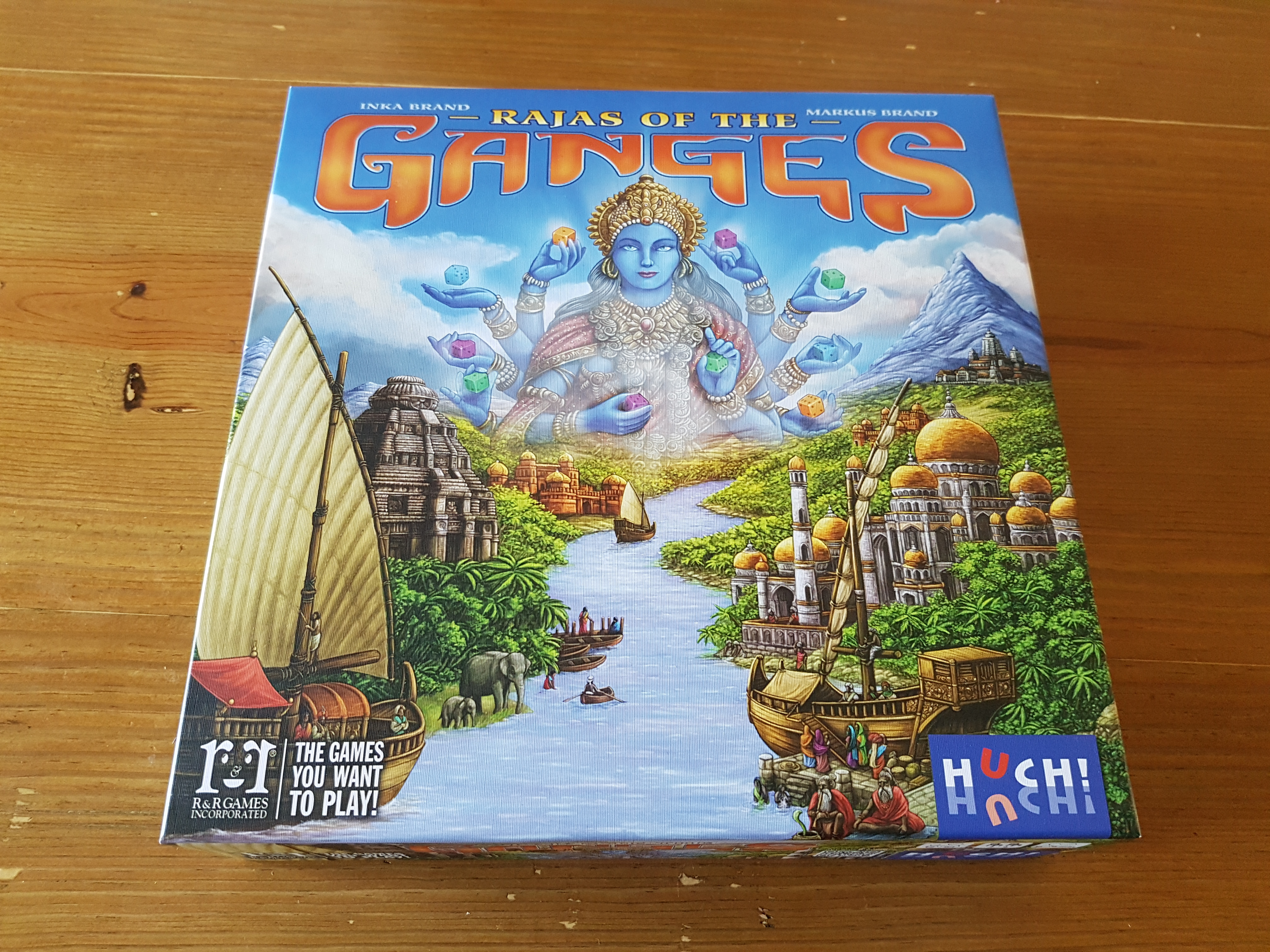

There is an air of elegance to Rajas of the Ganges that emanates from every single component. Starting from the first player marker, a small cardboard elephant, to the chunky and awesome to roll dice, a lot of love and attention has been paid to make the game beautiful. Yes, the board is busy but the illustrations beneath are a visual treat every time the game hits the table. It looks like it should, a celebration of the wonders of India and the Ganges river.

For the most part the rules are intuitive, with a great use of iconography to make remembering exactly what each action space does on the board easy. There are a couple of exceptions to this that made me dive for the rulebook on multiple occasions, just to make sure I was correctly following the rules. Unlike in Carcassonne not all roads on province tiles must connect just one back to the residence. It allows a slightly disjointed estate that doesn’t intuitively keep the illustration flowing. The other major oddity is the fact there are 6 workers of each colour in the game yet the rules state only 2 additional can be earnt. Having additional workers is always an advantage by I struggle to see why players shouldn’t be allowed to try to get all six.

A range of additional items are included in the box, which are effectively mini-expansions to enable players to change things up slightly. One of these modules sees the bonuses on offer along the river randomised. The issue is these tokens add to the setup time while only offering a bit of variation as a result. Due to this, they rarely leave the box. On the other hand, if you play enough of the game back-to-back they would help keep the game fresh.

Rajas of the Ganges is a worker placement tile first and a dice rolling game second, yet the designers have struck a balance between the two. Players get the fun of rolling dice, without the worries that bad luck could steal a victory away from them. It is hard not to be in awe of the illustrations of the board and the general production quality of the game. It helps the game stand out from the crowd with not many games utilizing this theme. There is a lot going on from the variety of actions to the sprawling personal estates though the game manages not to create a disjointed feeling between the individual and communal areas of play. I may normally claim I hate dice, or at least they hate me, but Rajas of the Ganges has proven if something is used correctly it can be great.

[Editor’s Note: Raja of the Ganges was provided to us by Asmodee UK for review purposes. The game is currently available on 365 Games for £39.99. It is also available from local UK board game stores, find your local store here]